THE HISTORY & SPIRIT

Chocolate is a divine, celestial drink, the sweat of the stars, the vital seed, divine nectar,

the drink of the gods, panacea and universal medicine. – Geronimo Piperni

ALONG THE LINES OF HISTORY

From the time of its discovery by the Olmecs of Mesoamerica in 1500 B.C., Theobroma cacao has served many functions, used primarily as a source of food (Coe & Coe 34). Grown in pods attached to the trunk of a rather peculiar looking tree, the Olmecs recognized that there was more than met the eye to this peculiar plant. As they cracked open the pod to reveal a sweet, gelatinous pulp, they took more notice of the seeds within the milky substance, and began to process those seeds to create the very first iteration of cacao, or “kakawa” (Coe & Coe 35). As empires rose and fell, the subsequent Mesoamerican civilizations of the Izapan, Maya, Toltecs, and Aztecs also coveted cacao for its properties. Consumed primarily in the form of a frothed drink, it was a prized possession and available only to the elite—for it was godly potion that would grant energy and power, and was used in many rituals to appease their deities (Coe & Coe 34). These attributes were considered more than simply advantages; in these times, food and prayer were the only sources of medicine (Lippi). Source

FROM MEXICO TO EUROPE

- Cacao first appeared in the Olmec tradition around 2000 - 1500 BC. in today's region around Mexico.

- Only recently archeologists found an artifact in Ecuador, that is 5.700 years old and dates the history of Cacao back a 1.500 years earlier. Read an article

- While in South America the sweet pulp was cherished for beverages, the whole bean was favoured in Central America.

- Pataxte (Theobroma bicolor) and cacao (Theobroma cacao) were a powerful ritual pair among Highland Maya groups.

- Cacao was used as a means of payment in Central America. When the Spaniards discovered the value of Cacao, they called it black gold 'oro negro' & seeds of gold 'pepe de oro'

- The maximum storage period is about three years, which made it the ideal money, because in its nature, free to flow, it had to be used and brought into the cycle of commerce. At the end of the cycle, the beans were peeled and eaten.

- The big change came with Hernan Cortes, who seized Mexico in 1519. According to some sources he brought Cacao to Spain in 1528, yet there is some unclarity. Cortes wrote: "The divine drink which builds up resistance and fights fatigue. A cup of this precious drink permits a full day without food."

- The Europeans added sugar, whereas the locals preferred it bitter. However, evidence of how Cacao was drunk differ as Cacao was used over centuries by peoples in South and Central America.

- Van Houten developed a method to de-fat cacao (from about a 50% fat content to 27%) and to alkalize it (called dutching) in 1815. This was the beginning of 'large-scale, cheap chocolate', with a patent granted in 1828.

- Nestle succeeded in pulverizing milk in 1867. The first milk chocolate was produced in 1879, which marked the end of the sacred medicine of Cacao.

- Since early 2000 and more concentrated around 2012 a new global community has formed that uses Cacao in Ceremony in new ways.

MAYA & AZTEC

The word cacao originated from the Maya word Ka'kau', as well as the Maya words Chocol'ha. The verb chokola'j means 'to drink chocolate together'.

The Maya Maize God is pictured as a Cacao tree.

Source: Probably Popol Vuh

Cacao tree detail from a Mayan mural at Cacaxtla, Mexico, 9th century.

A Mayan Glyph for Cacao

The flower god (K'uh/Ahaw? Nik) sits between two cacao plants. Above his head is a quetzal bird. Drawing after Villacorta C. and Villacorta (1976:364).

Cacao was an intrinsic part of ancient Mayan and Aztec life, not just as a beverage or food, but as a pillar of their economies and an integral part of their religions, appearing in numerous spiritual ceremonies.

In the Mayan culture, cocoa was so highly regarded that the Maya developed a creation myth concerning human beings involving cocoa. Any time a plant is given divine status in a culture, it means that the plant is central to that culture. For the Maya, cocoa was an integral part of the fabric of their lives. They cultivated cocoa, they used cocoa beans as currency, they developed numerous preparations of cocoa, and they topped it all off with a creation myth concerning the central Mayan god, known as Heart Of Sky. Source: The Medicine Hunter

LIFE, BLOOD, CACAO · MAYA AND AZTEC MYTHS AND RITUALS

Cacao was an intrinsic part of ancient Mayan and Aztec life, not just as a beverage or food, but as a pillar of their economies and an integral part of their religions, appearing in numerous spiritual ceremonies—even death rites and sacrifices.

The spiritual link between cacao and the Maya is immediately apparent in their texts, although only a small handful remain of their bark codexes. The Popol Vuh or Book of Counsel, for example, includes many references to cacao. In one story, the severed head of a god is hung on a cacao tree. Another page depicts the maize god sprouting from a cacao pod. Cacao even features in their creation mythology: at another point in the Popol Vuh, when the gods are creating humans out of foodstuffs, cacao is one of those foods found in the Mountain of Sustenance (Coe 38-40).

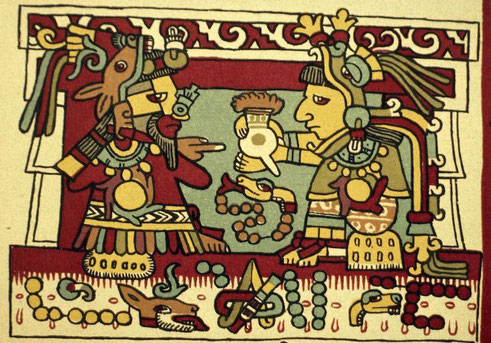

In Mayan creation mythology, humans are partially composed of cacao! In the Madrid Codex, an additional ancient Mayan text, four young gods bleed onto cacao pods, mingling the cacao and their blood.

If cacao was “a sacred offering to the gods combined with personal blood-letting through the piercing or cutting of their own flesh” to the Mayans, this page is an excellent reflection of that close bond (Seawright 7).

The link between blood (or heart) and cacao was not exclusive to the Mayans: in ancient Aztec society, cacao was given to sacrificial victims, often in ways that directly linked chocolate and blood. During the annual Aztec ritual in Tenochtitlan, a slave would be chosen to represent Quetzalcoatl. At the end of forty days, during which he had been dressed in finery and given all manner of good food and drink, he was informed of his impending death and then made to dance. If the temple priests saw that he was not dancing as enthusiastically or as well as they expected him to, he was given a drink of itzpacalatl, which was a mix of cacao and water used to wash obsidian blades. These were sacrificial blades, and therefore crusted in blood. The sacrifice would be rejuvenated and joyful after drinking this mixture of blood and chocolate, and dance to his death (Coe 103-104).

Cacao was also present in Aztec mythology. The Chimalpopoca Codex includes a myth similar to the creation tale in the Mayan Popol Vuh, in which the gods created man from maize, cacao, and other plants brought from the Mountains of Sustenance (Seawright 5). Additionally, the Codex Fejervary-Meyer, depicts a cacao tree as part of the universe:

“It is the Tree of the South, the direction of the Land of the Dead, associated with the color red, the color of blood. At the top of the tree is a macaw bird, the symbol of the hot lands from which cacao came; while to one side of the tree stand Mictlantecuhtli, the Lord of the Land of the Dead” (Coe 101).

This is one of many examples showing how ancient Mesoamericans linked their understand of divinity and spirituality with cacao (Seawright 5).

It is also yet another instance in which we see cacao as intrinsic to Aztec mythology and art, as well as connected to blood. Source

Itzamna, the young earth goddess Ixik Kab' & the flower god (Ahaw/K'uh? Nik) are pictured, letting blood from their ears onto two containers (cacao pods) on the ground. Drawing after Villacorta C. and Villacorta (1976:414). Source: Maya Codices

'Chocolate gets its sweet history rewritten'

It seems the history of Cacao is longer than assumed and offers many more surprises along the way.

COSMOLOGICAL WORLD TREE

In the Aztec culture Cacao was depicted as one of the major World Trees, watching the South, representing death, blood, and ancestors in the colour red. Death becomes an integral part of rebirth, the sun and the moon exist in an ever circling dance.

MEDICINAL USE - Food of the gods: cure for humanity? A cultural history of the medicinal & ritual use of chocolate.

The medicinal use of cacao, or chocolate, both as a primary remedy and as a vehicle to deliver other medicines, originated in the New World and diffused to Europe in the mid 1500s. These practices originated among the Olmec, Maya and Mexica (Aztec). The word cacao is derived from Olmec and the subsequent Mayan languages (kakaw); the chocolate-related term cacahuatl is Nahuatl (Aztec language), derived from Olmec/Mayan etymology. Early colonial era documents included instructions for the medicinal use of cacao. The Badianus Codex (1552) noted the use of cacao flowers to treat fatigue, whereas the Florentine Codex (1590) offered a prescription of cacao beans, maize & the herb tlacoxochitl (Calliandra anomala) to alleviate fever and panting of breath and to treat the faint of heart. Subsequent 16th to early 20th century manuscripts produced in Europe and New Spain revealed >100 medicinal uses for cacao and chocolate.

Three consistent roles can be identified: 1) to treat emaciated patients to gain weight; 2) to stimulate nervous systems of apathetic, exhausted or feeble patients; and 3) to improve digestion and elimination where cacao/chocolate countered the effects of stagnant or weak stomachs, stimulated kidneys and improved bowel function. Additional medical complaints treated with chocolate/cacao have included anemia, poor appetite, mental fatigue, poor breast milk production, consumption/tuberculosis, fever, gout, kidney stones, reduced longevity and poor sexual appetite/low virility. Chocolate paste was a medium used to administer drugs and to counter the taste of bitter pharmacological additives. In addition to cacao beans, preparations of cacao bark, oil (cacao butter), leaves and flowers have been used to treat burns, bowel dysfunction, cuts and skin irritations. Source

"The Maya drank its Chocolate hot and frothy that was produced by pouring the drink back-and-forth from a height or with a beater (molinillo)."

A MAYA RECIPE

The Maya drank chocolate as a frothy, hot and bitter drink, according to the following 2,000 year old recipe:

1. Mix the cacao paste with water

2 Add spices such as chilli peppers and cornmeal

3. Pour the concoction back and forth from cup to pot until it develops thick foam on top

4. Sweeten with honey or flower nectar

Cacao drinking vessel

A woman preparing cacao, 16th century

RITUAL USE

- In Maya times, drinking chocolate was one of the privilege of high status individuals as it was considered Food of the Gods

- It was a very precious substance and, therefore, reserved for the elite (the royal house, nobles, priests, highest government officials, military officers, great warriors, shamans, artist, merchants)

- It was supposed to be unsuitable for women and children

- Cacao was prepared by priests for religious ceremonies, seeds were offered to the gods

- Cacao was regarded sacred, as well as blood and we find many blood offerings in the context of cacao in ceremony

- Marriages required the ceremonial use of cacao due to its fertility aspects and was part of the the initiation of marriage negotiations

- Cacao was given for the birth of a child and was part of the baptism ceremony

Cacao served to an Aztec couple on their wedding day. Picture: National Geographic